The storytelling in Telltale’s The Walking Dead is magnificent, not because of the zombies, but because of something much simpler than all that. The choices you make in The Walking Dead have consequences. Cause and Effect. Action and Reaction.

Now I imagine some of you are jumping out of your seats, flipping tables, and yelling at your monitors. “Wait a minute,” you say. “Tons of games have consequences for player action!” Right?

Except they really don’t, at least not in any meaningful way. Fallout 3, for example, allowed your alignment to rise and fall, and this slightly affected what quests you could take, what perks you could get, and what 30-second ending you eventually got to see. But those aren’t really consequences; they are variables.

Sure, by some definitions of the word “consequence,” murdering 1,000 innocents in order to get a slight change in an ending cutscene is a consequence, but it’s not a very good consequence. It has no actual weight because you can always just go on YouTube and watch whichever ending you want.

But the majority of consequences in Fallout 3, or should I say lack thereof, actually make no logical sense. I could run around murdering everyone I see, and yet when I enter a new town, regardless of the fact that people have “heard” of me, everyone treats me like I’m not a threat. I could shoot Three Dog in the face, and everyone listening to the radio would know he’s dead and that I did it. Yet everyone treats me like the friendly neighbor next door. They should be terrified of me. They should be shooting me on sight, or at the very least treating me with a very cautions skepticism that comes at the end of a rifle barrel.

I am using Fallout 3 because it’s an example of a game that prided itself on story but had no real consequences for actions. Other games with moral choice systems like inFamous, BioShock, Mass Effect, Dragon Age, and even Heavy Rain suffer from the same problem to various degrees. But The Walking Dead is different. Because 90% of the game is dialogue and dialogue choices, your choices have to have weight for the game to mean anything. Characters treat you differently in their day-to-day conversations. Some don’t trust you. Some would take a bullet for you. It’s not some sort of black-and-white global variable that sets how good or how bad you are. It’s a nuanced set of relationships based on what you do and how you treat other people.

This is what all games with a story need. Otherwise, we have no right to call video games a form of “interactive media.” Because you aren’t really interacting with anything if there are no consequences. Sure, you can succeed or fail, but this isn’t interaction as much as it is a roadblock barring your access to the next non-interactive cutscene. That’s less like interaction and more like watching a movie where every so often a friend hits pause and forces you to play rock, paper, scissors.

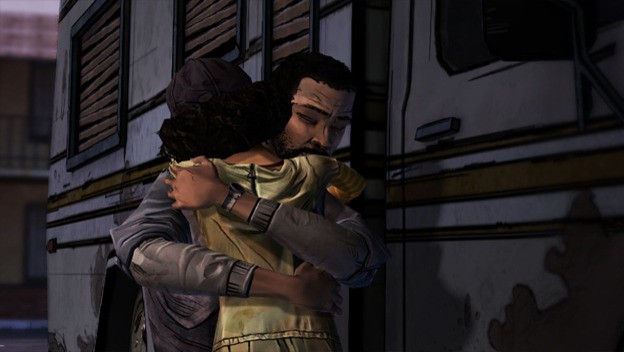

Interactive media is a powerful form of expression because it lets viewers inject their own feelings, words, and actions into the work of art. The Walking Dead encapsulates this perfectly. Lee Everett isn’t just Lee Everett at the end of the five episodes. He’s you. Unless you were purposefully attempting to play Lee to fit some sort of other personality, you probably made decisions that fit with your own morality. You befriended people that you would trust in real life and rejected people who rubbed you the wrong way. Maybe you tried to play the great uniter, helping everyone to get along when times were tough. Maybe you chose sides right off the bat, keeping your friends close and your enemies closer. Maybe you played the lone wolf, caring about no one except you and the girl you have come to call your own. All are valid ways to experience The Walking Dead, but only because the game allows you to do so. Telltale could have just as easily made Lee Everett a canned personality with set responses and relationships that don’t change based on your input, but the game would be a lot less compelling as a result.

Now, not every game should give you this much flexibility. In fact, the constraints put on your choices can do a lot to flesh out a character. Spikey-haired JRPG protagonists should be forced to be optimistic, and battle-hardened space marines should be forced to be overflowing with testosterone.

However, I would still like to see some sort of consequences for the actions I take in these games. If a JRPG protagonist spends all day killing wolves, it would be interesting if the townspeople treated him as some sort of peculiar wolf-killer. Maybe it would be nice if the Hunters’ Guild would give out a reward for helping them out, thus making all hunters regard that character better across the world. If my Space Marine lets an entire platoon die in an alien shootout, I want someone to mention that. I want someone to hold that character responsible instead of going about their business as if ten good young men didn’t just lose their lives to giant robot space scorpions.

So that’s it. That’s the one element of The Walking Dead’s story that I want to see more of. I want to see actions have consequences. Maybe critics will respect interactive media more when our consequences are more than just “Die and respawn at the last checkpoint.”

| By Angelo M. D’Argenio Lead Contributor Date: November 28, 2012 |